Lit-history

From oral tradition to audiobook, The Epic of Gilgamesh has transcended time and culture, leaving an impact on humanity throughout the ages. At Lit-History, you will be immersed in history, literature, and culture, and you will leave with a solid foundation for interpreting other timeless pieces at your own leisure. Come, let us go back in time and EXPLORE!

Mesopotamian Communications Systems and

The cultural context of gilgamesh

,

Modes of Communication

Physical Confrontation and Action

,

Modes of Communication

Oral Tradition

,

The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Iliad

How each epic preserves or interprets historical events

,

Works cited

,

Contact

Send me a message

Thank you

Aristotle said, "It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it." Thank you for opening your mind to new thoughts, ideas, and perspectives. Knowledge is power, and empathy is not weakness. This floating rock will keep spinning with or without you, so leave a legacy of kindness.

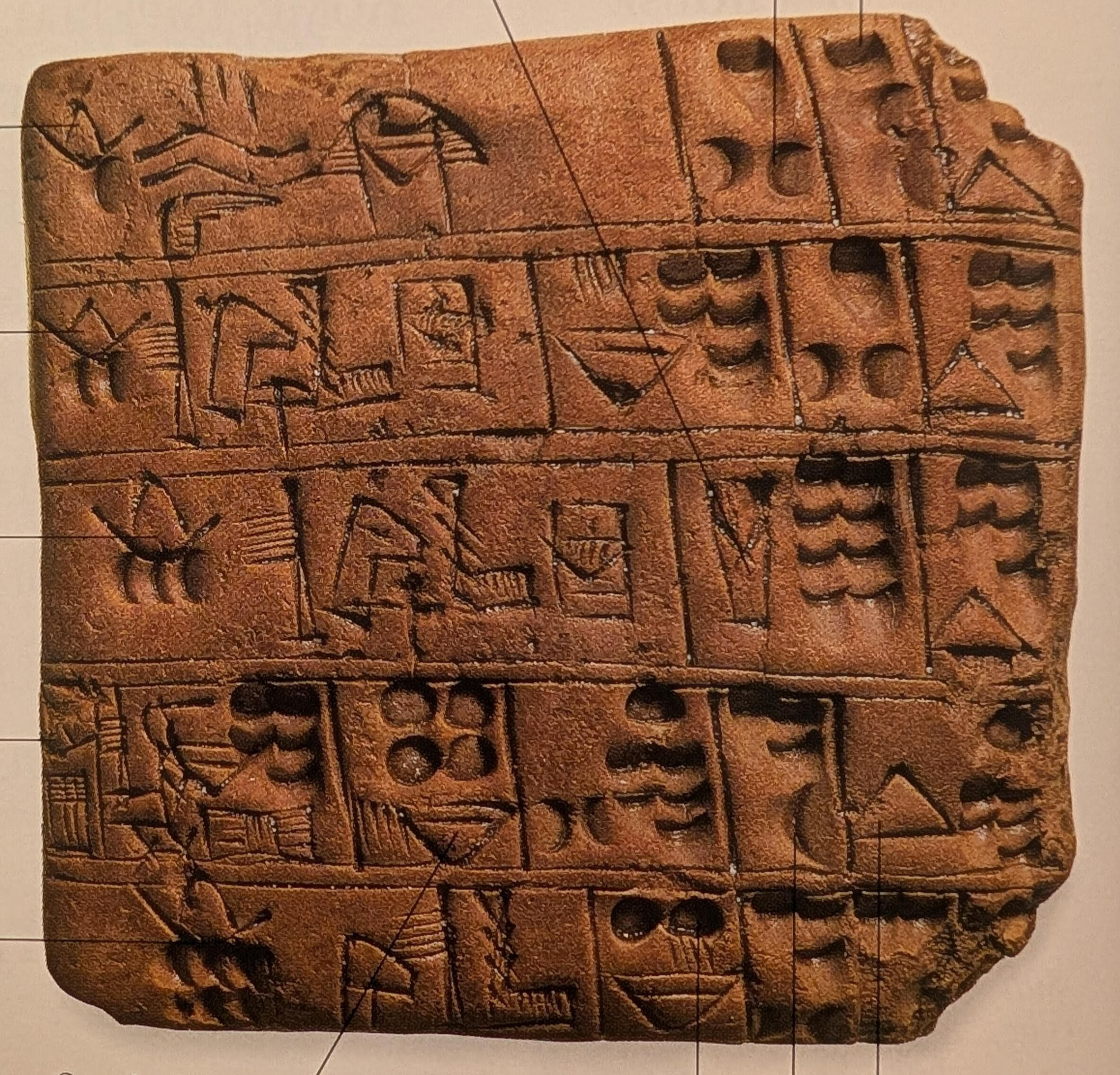

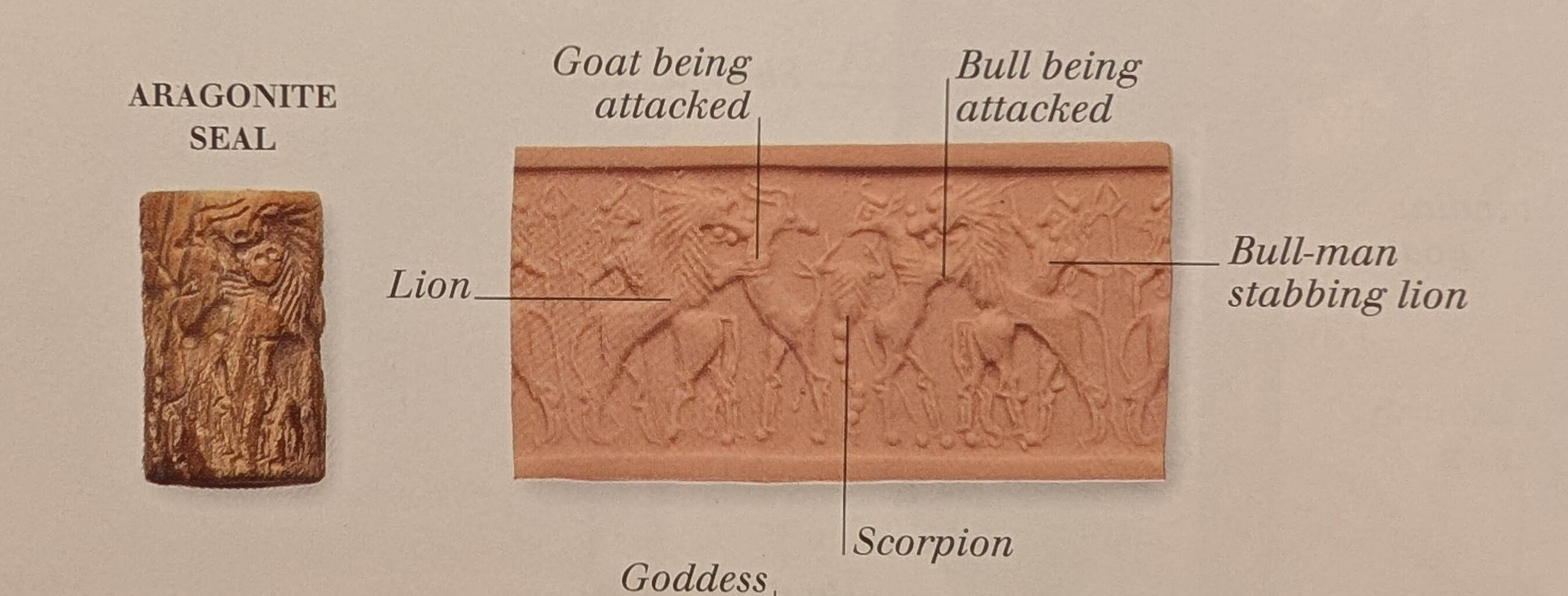

Mesopotamian communication systems and the cultural context of Gilgamesh

Oral TraditionAnatomically modern humans have wandered the earth for more than 300,000 years! Sometime after communicating with grunts and gestures, but before the first writing systems were invented, Homo sapiens passed on knowledge and information through oral tradition. The period before writing systems existed is often referred to by anthropologists as prehistory (Renfrew, p. 14)The Epic of Gilgamesh is thought to have been passed down orally for at least several centuries before being recorded in the first writing system, cuneiform. However, the epic continued to be told in oral tradition even after written language became available, being “read or recited to the illiterate public for entertainment and edification” (Cotterell, p. 95)Cuneiform TabletsAbout 5,000 years ago, around 3,000 BCE, ancient Mesopotamians created the first written language called cuneiform. It involved the use of a stylus tool with a wedge-shaped tip to press markings into clay tablets. Sometimes, these tablets would include a signature “on a cylinder seal—a small, engraved, cylinder shaped stone—that was rolled across clay tablets to produce a continuous pattern.” (DK Publishing, p. 6)Cuneiform was used for many purposes: to record information such as laws and traditions so that they would not be lost, to communicate current information such as letters or texts used to train scribes, and even to communicate with the gods in sacred texts or amulets (Renfrew p. 162)ScribesAfter cuneiform came into being, there arose a need for scribes. Before printing presses were invented, the only way to copy information was literally to copy that information. There were schools for scribes where, under expert leadership, texts that had been passed down would be “reworked, rewritten and their form standardized into a certain number of tablets per composition with a specific number of lines to each tablet.” (Cotterell, p. 95) It was at this point that The Epic of Gilgamesh was transformed into a version consisting of 12 tablets.

Modes of Communication

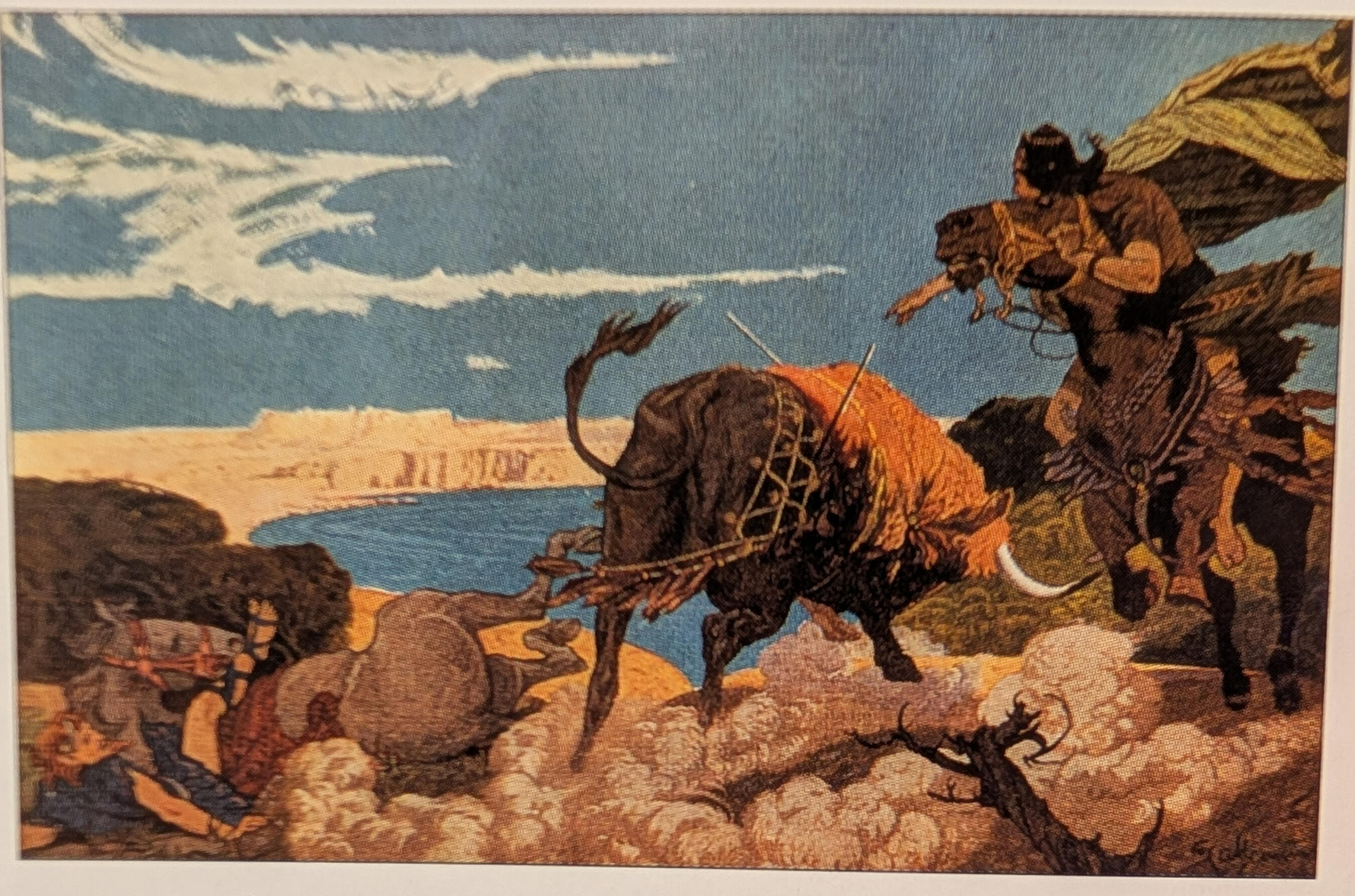

Physical Confrontation and ActionThere are many modes of communication in The Epic of Gilgamesh to be analyzed, such as monumental inscriptions and oral storytelling, but this page of Lit-History focuses on physical confrontation and action. Exciting!Early on in the epic, Gilgamesh is not necessarily a kindly, kingly character; instead, he is obnoxious, arrogant, and often abuses his power. In order to bring the demigod back down to earth, the gods send an unruly wild man named Enkidu to put him in check. Upon their first meeting, Enkidu attempts to block Gilgamesh from entering a wedding, who probably had intentions of sleeping with the bride before her groom had the chance to consummate their nuptials. Gilgamesh and Enkidu become entangled in an all-out drag out to prove their strength. After shattering doorposts and shaking walls, neither one willing to give up or in, “They kissed each other and made friends” (Gilgamesh, Tablet 2 line 115).Later on, after Gilgamesh slays the monster Humbaba, the goddess Ishtar tries to seduce Gilgamesh saying, “Come, Gilgamesh, you shall be my bridegroom!” (Gilgamesh, Tablet 6 line 7). He declines her advances, and to add insult to injury, launches insult after insult. In her hurt and anger, she sobs and pleads before her father god Anu to send the Bull of Heaven to kill him. Gilgamesh and Enkidu fight the bull, the battle ending with Enkidu delivering the fatal blow.The Epic of Gilgamesh is chock-full of thrilling encounters and battle scenes. This tale suffers no shortage of witty banter, harsh words, and epic altercations!

Modes of Communication

Oral TraditionPreviously on Lit-History, we explored physical confrontation as a mode of communication in The Epic of Gilgamesh. Let us take a look at oral tradition and how it helps to shape both public understanding and legacy.Gilgamesh was a real living being in ancient Mesopotamia, though how much is true of the legends circulating about him is unknown. What we do know for sure is that centuries before written language appeared, information, legends, and history were passed down orally from generation to generation. Oral tradition is how cultural memory was kept alive, even if some of the information became lost or was changed over time, similar to the children’s game telephone. Sharing these stories with kith and kin helped to create strong social bonds, as well as foster identities within the community. Some scenes or ideas relayed in these epics may have seemed farfetched; however, lessons about morals, ethics, and values could be deduced from the information being passed down, further strengthening cultural identities and ensuring that which was important to them was preserved, even as humans were adapting to rapid changes in the environment, society, and to the general ways of living.To recap, we cannot be absolutely certain how much was true of the tales about Gilgamesh. We do know that he really was king of Uruk sometime around 2700 BCE and he was the protagonist of many Sumerian legends. Passed down orally for several centuries, Babylonian scribes eventually “wrote” down those stories using cuneiform beginning in around 2000 BCE. Today, sadly, there are only five known Sumerian stories about Gilgamesh that have survived over the millennia: Gilgamesh and Huwawa; Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven; Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld; Gilgamesh and Aga; and The Death of Gilgamesh (Spar, 2009).

The Epic of gilgamesh and the iliad

Both The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Iliad weave together real culture and historical events with narratives of fiction and fantastical beings.We cannot be certain about how much the demigod is factually represented in the epic, but around 2700 BCE, Gilgamesh was king of the city-state of Uruk, or Erech, located in modern-day Iraq (Puchner, p. 90). It is widely accepted by scholars that he was responsible for building the city walls around the great city of Uruk.Many times throughout his epic tradition The Iliad, Homer mentioned people, places, and events that were actually historical. Though Iliad was not an historical place, Homer used this title to represent an ancient city, Troy, which was located in northwest Asia Minor (Cotterell p. 141), now modern day Turkiye.Homer also mentioned Crete and called it “a land called Crete lying in the midst of the wine-dark deep, which is fair and fertile and girdled by the sea” (Homer, Book 19 lines 172-177). In an article about the Minoans, it is stated that “The Homeric record shows what has now become clear from other evidence, that Crete was prestigious, well-populated and prosperous in the later Bronze Age.” (Cotterell, p. 204)

Works cited

Cotterell, Arthur. “Babylonia.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations, edited by Arthur Cotterell, The Rainbow Publishing Group Limited, 1980, p. 95Cotterell, Arthur. “The Evolution of the Alphabet.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations, edited by Arthur Cotterell, The Rainbow Publishing Group Limited, 1980, p. 171Cotterell, Arthur & Rachel Storm. “Heroes and Quests.” The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology, edited by Emma Gray, Hermes House, 2002, p. 322.Cotterell, Arthur. “The Minoans.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations, edited by Arthur Cotterell, The Rainbow Publishing Group Limited, 1980, p. 204Cotterell, Arthur & Rachel Storm. “Myths of the Flood.” The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology, edited by Emma Gray, Hermes House, 2002, p. 282.Cotterell, Arthur. “Troy.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations, edited by Arthur Cotterell, The Rainbow Publishing Group Limited, 1980, p. 141DK Publishing. “Mesopotamia: Everyday Life.” The Visual Dictionary of Ancient Civilizations. Dorling Kindersley, 1994.“The Epic of Gilgamesh.” The Norton Anthology of World Literature, Martin Puchner, 5th ed., vol. A, W.W. Norton, 2024, p. 90-144.Renfrew, et al. Archaeology Essentials. 5th ed., Thames & Hudson, 2023.Spar, Ira. “Gilgamesh.” The Met, 1 April 2009, www.metmuseum.org/essays/gilgamesh